PhD Student Advising Articles written by Shannon E. Williams, Assistant Dean for Student Engagement at the Schar School

In 1948, the World Health Organization proposed a definition of health that recognizes its mental and social aspects in addition to the physical components. Today, the WHO still relies on this same definition to gauge the well-being of people all over the globe (World Health Organization and United States 1946).

Including graduate students.

During their studies, students encounter unexpected life events and grapple with unfamiliar stressors. Add these to the predictable pressures of school and students can find themselves thrown out of balance. While academic rigor is the foundation of scholarly productivity, research into student outcomes supports what we witness anecdotally: those students who take care of their well-being are more likely to stick with their programs and produce higher quality scholarship than those who do not attend to their physical and mental health (Pascarella 1991; Becker et al. 2009).

One of the foundational frameworks for wellness had its start in a university health center (Hettler 1976). On an interconnected campus, it becomes clear that such things as quality of life, attitudes, relationships, and access to resources all contribute to health. A university is the ideal setting for establishing supportive resources students can use as they seek the balance necessary for long-term success. This series of PhD Student Advising Articles discusses the roles that social connection, stress reduction, and collaboration with peers all play in academic achievement.

It is never too late to start. At any point during your graduate studies, you can adapt your behavior to the changing circumstances of your life.

What is wellness?

It is easier to begin with what wellness is not. It is not the absence of disease, as all ages of people with many kinds of illnesses can live with vitality. It does not rely on high expectations of fitness, productivity, or mental soundness. It is not a fixed state or a destination. While the concept may encompass such physical features as exercise, diet, and sleep, it is far more than a narrow notion of health.

As an orientation rather than a quantifiable condition, wellness is the collection of thoughts and behaviors that contribute to soundness, vitality, and functioning. It can be defined as “a conscious, deliberate process that requires a person to become aware of and make choices for a more satisfying lifestyle” (Swarbrick 1997), as well as “the process of creating and adapting patterns of behavior that lead to improved health in the wellness dimensions and heightened life satisfaction” (Johnson 1986).

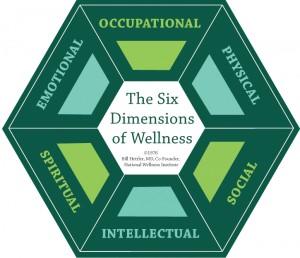

Several configurations of these wellness dimensions have been proposed. The most straightforward considers the following six realms of a person’s life: social, occupational, spiritual, physical, intellectual, and emotional.

A more thorough description of the model is available through The Wellness Institute (Hettler 1976).

How Balanced is Your Wellness Wheel?

Consider the dimensions of wellness as sectors between the spokes on a bicycle wheel. If a bike is ridden regularly, the pounding of the tire on the road surface can throw off tension. Irregularities can form over time, wear down brake pads, and damage the rim. Every so often, and especially after hard rides, cyclists have to “true” their wheels. Lifting the bike, a rider gives the tire a spin. Peering carefully between the brake pads may reveal wobbles where adjustments should be made. Small tune-ups along the way can prolong the life of the components and keep the whole machine moving at optimal efficiency.

Like serious cyclists, graduate students cover great distances over rough terrain in a compressed period of time. The rigors of academic life take their toll.

The eight weeks of summer still ahead are an ideal window for delving into research and making headway on professional goals. It is also a good opportunity to pull over and check your condition. Looking carefully at your whole system and its component parts can allow you to identify uneven spots. The minor adjustments you then make might improve your performance in the program and contribute to your long-term success.

Assess Your Wellness Wheel

Take a few minutes and examine each wellness dimension. On a simple scale of 1-10, determine how robust each aspect is. As a cyclist would look at a slowly spinning tire, evaluate with a keen eye. Assess each area on its own, avoiding your aspiration to attend to that part of your life. Do your best to gauge your allocation of time and mental energy, the features present and missing, and your sense of fitness in each aspect of your life.

The following questions may help you examine the dimensions:

- Social: Do I have a strong, interdependent support system? Who comprises it? How often do I spend time with others, what do we do together, and what is the quality of our interactions?

- Occupational: Does my work match my values and lifestyle? Am I expanding my career skills? What is the state of my finances? Do my current choices fit with my long-term goals?

- Spiritual: How is my sense of connection to a greater purpose? Are my behaviors consistent with my values and beliefs? Do I nourish my sense of belonging and contribution?

- Physical: Do I maintain a consistent and enjoyable exercise plan? Am I on top of my medical and dental care? How am I attending to sleep, nutrition, weight, and stress management? How reliant am I on caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, and over-the-counter drugs?

- Intellectual: Am I exploring my academic work with focus and organization? Do I seek challenging opportunities and build new relationships in order to expand my knowledge? What contributions do I make to my field?

- Emotional: Can I realistically identify my limits and cope with stressors? Do I take responsibility for my feelings, thoughts, and behaviors? Where and how do I express emotions and explore challenging questions?

You may choose to plot the points of your assessment on a graph for a visual representation. Don’t be surprised if some aspects almost entirely eclipse others. This is a normal distribution for graduate students. Of course, imbalance is neither sustainable nor a foundation for good scholarship. Research is just beginning to bear this relationship out. One study correlates health-promoting behaviors not only with better health outcomes but also with higher GPAs (Becker et al. 2009).

True Your Wheel

How might you correct the spokes a bit here or there to center your wheel? Summer can allow you breathing room to take care of neglected aspects of yourself. Get started with the following suggestions:

- Social: Use a Mason student discount at a local restaurant or business and meet up with a friend. Combine this with a physical component by organizing a walk with a group of classmates.

- Occupational: Peruse the funding sources page on the Schar School website or begin sketching out an idea for a poster or presentation at an upcoming academic conference.

- Spiritual: Visit the National Arboretum in D.C. or find a volunteer opportunity to help strengthen your community.

- Physical: Explore some of the fitness options available to local students. Squeeze in a mid-afternoon stretch or go to bed just 15 minutes earlier for one week.

- Intellectual: Attend an event listed on Linktank.

- Emotional: Commit to writing a bi-weekly entry in a personal journal focused on non-academic reflection.

Wellness is an orientation comprising many interdependent aspects of a person. Any positive change in one area of your life can contribute to optimal performance across many dimensions. A major overhaul is not required. The Currents piece on healthy habits discusses the importance of taking baby steps in the direction of measurable, attainable goals. Attend to one small adjustment at a time. This summer, find a single spoke within one dimension and tweak it just enough to draw the wheel towards it center.

—

Works Cited

Becker, Craig, Nelson Cooper, Kemal Atkins, and Suzanne Martin. 2009. “What Helps Students Thrive? An Investigation of Student Engagement and Performance.” Human Kinetics Journals 33 (2) (October): 139–149.

Hettler, Bill. 1976. “The Six Dimensions of Wellness Model”. The Wellness Institute. https://nationalwellness.org/resources/six-dimensions-of-wellness/.

Johnson, Jerry. 1986. Wellness: A Context for Living. New Jersey: Slack Incorporated.

Pascarella, Ernest T. 1991. How College Affects Students: Findings and Insights from Twenty Years of Research. 1st ed. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Swarbrick, Margaret. 1997. “A Wellness Model for Clients.” Mental Health Special Interest Section Quarterly 20 (March): 1–4.

World Health Organization, and United States. 1946. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Official Records of the World Health Organization.